MO Diagrams

MO diagrams

Electron waves

The world really is strange. It is stranger than most people realize. Back in your Junior High Science class, you were probably told that light is both a particle and a wave. We call that the duality of light. This dual nature is not only true about light, but it is true about most of nature. This is the strangeness that we explore in a field called quantum mechanics.

For now, I want us to focus on the wave-particle duality of electrons. One way to think about electrons is that they are little particles orbiting the nucleus. This is a fairly good model that many of us have in our minds, the Bohr planetary model. But, the interesting thing is that electrons are also waves! Let’s focus on two very simple waves. Think of a guitar string. If I pluck a guitar string, it vibrates up and down.

If I combine these, the string vibrates so fast that it looks something like this.

It has zero nodes in the center of it. This simple vibrational shape is spherical in nature and leads us to the shape of the simplest electron orbital, the s-orbital.

s-orbital

If I put my finger down in the middle of the guitar string and pluck it, I get a wave where when one side is up, the other side is down. A moment later, it switches which side is up and which is down.

When the string vibrates fast, it looks something like this.

It has one node in the center of it. This vibrational shape has two lobes of equal size. It leads us to the shape of another electron orbital, the p-orbital.

p-orbital

These orbital waves can be described with mathematical functions—just like all waves can. We call this mathematical function for the wave the wavefunction (Ψ). These mathematical functions can be added together or subtracted. Intuitively, you understand this about waves.

For example, a child on a swing set moves forward and backward. This motion is a wave-like motion. When children are learning to swing on a swing set, they are taught to kick their legs out when they are moving forward and bend at the knees and put their feet down when they are moving backwards. This motion of their feet is also a wave. They are taught to do this so that their feet wavefunction can be added to the wavefunction of the swing. This is constructive interference of these waves. This increases the amplitude of the wave, and the swing goes higher and higher.

Many children get confused when learning this, though. If instead they kicked their feet straight out when they were going backwards and bent their knees putting their feet down when they were going forwards, their feet wave would be opposite the swing’s wave. This is destructive interference. hildren who swing this way will not be swinging for long. When the wavefunctions are subtracted from each other, they get cancelled out.

Because they are waves, when electron orbitals meet and overlap, they can add constructively or destructively. This can happen when orbitals overlap on the same atom (to make hybrid orbitals) or when orbitals on two different atoms overlap when the atoms come together (to make molecular orbitals).

Sigma and Pi Bonds

When two atoms come together, the electron orbitals on the atoms can overlap. This constructive overlap of electron density between two atoms makes bonding molecular orbitals, also called bonds. There are two main types of bonds we will deal with in organic chemistry, sigma and pi bonds. A sigma bond is directly between two atomic nuclei. Or, a more technical way to describe it is the electron density lies on the internuclear axis. A pi bond has electron density above and below the internuclear axis.

Sigma and pi-bonds

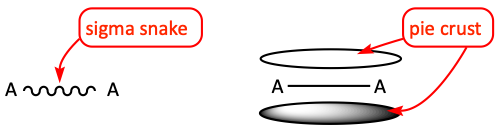

A mnemonic to help you learn these at first is to think of the first, single bond between two atoms as a snake, the sigma snake. This can help you think of a sigma bond. The second bond is split into two regions, above and below the internuclear axis. A pi bond may remind you of a pie crust.

Sigma and pi-bond mnemonics

We’ve learned that hybridization is a mixing of atomic orbitals on one atom. We need to look at how two or more atoms come together to make bonds and form molecules. We mix hybrid and/or atomic orbitals to make these molecular orbitals. These bonds that we form between atoms are called molecular bonds.

Atomic orbitals are s and p orbitals on individual atoms.

Hybrid orbitals are sp, sp2, s p3 orbitals that are mixed from the s and p atomic orbitals on the same atom.

Molecular orbitals are a mixing of atomic and hybrid orbitals on atoms to make bonds between atoms. This is how we make molecules. But, interestingly, it is a little more complicated than that. These molecular orbitals can be spread out over more than two atoms. This may be a new concept for you. It will seem strange at first, but if you think about it enough, it will begin to make sense. Another strange feature of molecular orbitals is that for every bonding molecular orbital (also called a bond) that forms, an antibonding MO also forms. Sometimes an antibonding MO will have electrons in it. Sometimes it does not. When an antibonding MO has electrons in it, it is the opposite of a bond, it is a bond breaker. Again, this is a strange concept to you because it is new, but after a while, it begins to make sense.

We describe the energies of bonds and antibonding MOs using a diagram called a molecular orbital diagram (MO diagram). The MO diagram shows the energies of molecular bonds, molecular antibonding MO, and atomic orbitals, as well as which orbitals contain electrons. We will begin by showing some very simple molecules and describe their bonding using MO diagrams.

When making MO diagrams, there are a few rules we follow.

Rules for Molecular Orbital (MO) diagrams.

1. The number of atomic orbitals equals the number of molecular orbitals formed.

2. The number of bonding molecular orbitals equals the number of antibonding molecular orbitals.

3. The bonding molecular orbitals are lower in energy than the atomic orbitals. The antibonding molecular orbitals are higher in energy than the atomic orbitals. The amount of energy saved putting electrons in bonds is equal to the amount of energy lost putting electrons into antibonding MOs.

4. Any orbital, whether an atomic orbital or a molecular orbital can contain at most two electrons.

Dihydrogen Molecular Orbital Diagram

This is a hydrogen atom. It has a nucleus with one proton in it. But, for now, we are interested only in its electrons. It contains one electron in a 1s atomic orbital.

Hydrogen atom 1

This is another hydrogen atom with one electron in a 1s atomic orbital.

Hydrogen atom 2

What happens when these two hydrogen atoms approach each other to try to make the molecule H2? There are two possibilities for how the two hydrogen atoms can interact. When the electrons of the hydrogen atoms (which are waves) begin to interact, they can constructively interfere with each other or destructively interfere with each other. When they constructively interfere, the electron waves add to each other and form a lot of electron density between the two hydrogen atoms, helping hold them together. We call this a bond. In fact, since this electron density is along the internuclear axis, it is called a sigma bond. When electrons from the two hydrogen atoms are out of phase with each other and destructively interfere with each other, the electron density is cancelled out between the two hydrogen atoms and the electron density is concentrated outside of the hydrogen nuclei. This is called an antibonding molecular orbital. This does not help hold the two hydrogen atoms together.

The sigma bond is lower in energy than the energy of the hydrogen atoms s-orbital atomic orbital. It is also lower in energy than the sigma antibonding MO. This leads to the following molecular orbital diagram for dihydrogen (H2).

Molecular orbital diagram for dihydrogen

In the MO diagram, lower energy orbitals are lower in the diagram and higher energy orbitals are higher in the diagram. The atomic orbitals are on the left and right side of the diagram. In this case, the atomic orbitals are the 1s atomic orbitals of the two hydrogen atoms that come together. These atomic orbitals each have one fishhook arrow in them to describe the one electron in each of the 1s orbitals.

In the middle of the diagram are the molecular orbitals. The constructively overlapping sigma bond is lower in energy and the destructively overlapping sigma antibond is higher in energy. Antibonding orbitals are designated with a “*”, so the antibonding orbital of H2 is represented as σ*.

The total number of bonds between two atoms is called the bond order. A bond order of 1 is a single bond, a bond order of 2 is a double bond, a bond order of 3 is a triple bond.

Bond order (B.O) = Number of bonds – number of antibonding MOs

Since each hydrogen atom contained one electron in its atomic orbital, there is a total of two electrons the molecule will have. These electrons fill up the molecular orbitals starting at the lowest energy orbital and move up from there. So, the two electrons are placed into the sigma bond orbital. This means that for the molecule, two electrons are in the sigma bond making a single bond between the two hydrogen atoms. There are no more electrons, so the sigma antibond orbital (σ*) is empty.

Bond order = 1 full bond – 0 full antibonding MOs = 1

H2 has a single bond between the two hydrogen atoms and can be symbolized as H-H.

Dihelium Molecular Orbital Diagram

What happens when two helium atoms come together to try to make a dihelium molecule, He2? A helium atom contains two electrons in its 1s atomic orbital.

Sigma and pi-bonds

Molecular orbital diagram for dihelium

The helium atoms provide four electrons that must go into the molecular orbitals. Two electrons can go into the sigma bond. Each orbital, even molecular orbitals, can hold a maximum of two electrons in it. Therefore, the sigma bond is full with two electrons. The remaining two electrons must go into the antibonding σ* orbital. When two electrons go into an antibonding orbital, a bond is broken.

Bond order = 1 full bond – 1 full antibonding MO = 0

He2 has a bond order of 0. He2 is not held together. The He atoms do not bond together. This is why He is a noble gas and does not form a diatomic molecule.

Now let’s focus on pi bonding, in particular, conjugated double bonds.